July 2025 will be remembered as a month when climate change’s economic consequences hit home around the world. From record-smashing heat waves to catastrophic floods and wildfires, extreme weather events have disrupted lives and livelihoods on every continent. Preliminary data indicate that the first half of 2025 alone saw 19 separate billion-dollar weather disasters globally, causing an estimated $134 billion in damage (with an unprecedented $81 billion of that insured).

Introduction: A Summer of Climate Shocks

July’s onslaught of disasters only added to this toll, underscoring the growing financial risk of a warming planet. In the United States, for example, extreme weather has already caused between $375 and $421 billion in combined damages so far this year. Each heatwave, flood, and fire brings not just humanitarian tragedy but also a hefty price tag – straining government budgets, disrupting businesses, and burdening households.

In this dossier, we provide a narrative-driven overview of the past month’s climate-related economic shocks. We’ll survey the globe and drill down by sector – from agriculture and energy to infrastructure, insurance, labor, health, and tourism – to reveal how July 2025’s extreme weather events translated into real economic costs. All figures and facts are presented in clear, accessible language, with important data and estimates cited from recent reports. The goal is to help general readers grasp the scale and scope of climate change’s financial impact, without jargon, but with plenty of evidence.

Global Overview: Billion-Dollar Disasters on the Rise

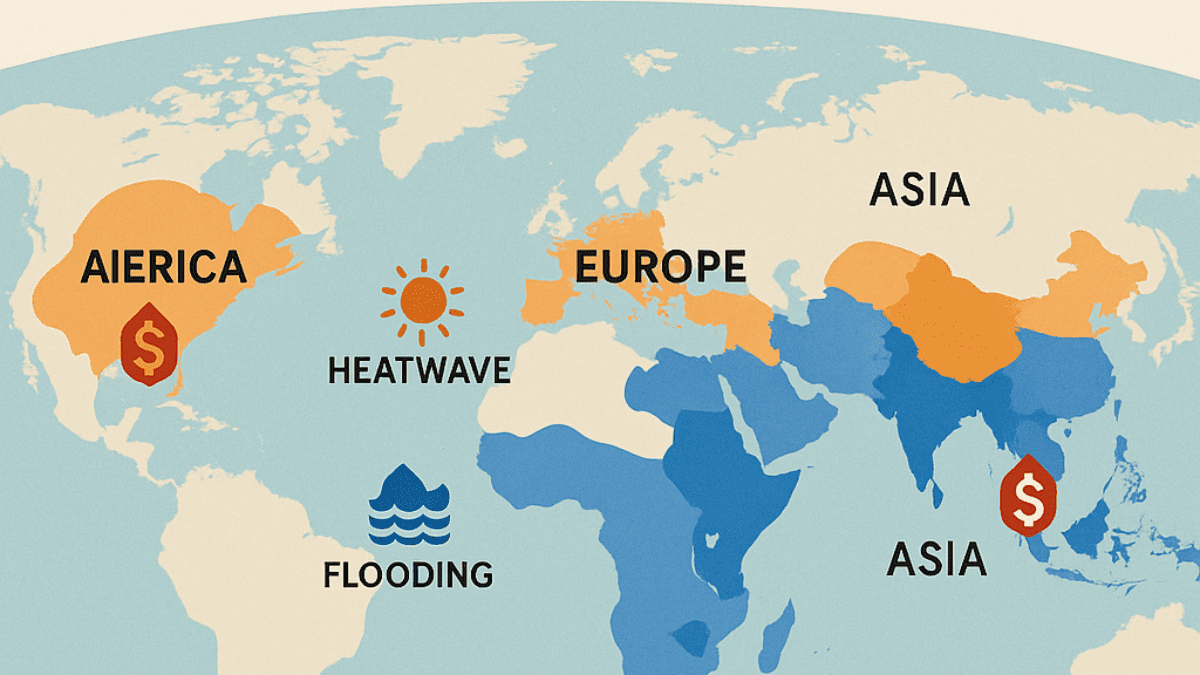

It’s no exaggeration to call July 2025 a “global boiling” point for the economy. Meteorologists confirmed that parts of the world experienced some of the hottest temperatures on record during the month, fueling deadly heatwaves across Europe, North America, and Asia. These heatwaves did more than break temperature records – they also dented economic output, as businesses curtailed hours and workers struggled in the sweltering conditions. One analysis estimates that recent heatwaves could shave about 0.5 percentage points off Europe’s GDP growth, about 0.6 points off U.S. growth, and as much as 1.0 point off China’s, compared to a scenario without such extreme heat. In practical terms, just one day of temperatures above 32 °C can be as economically disruptive as half a day of lost work (such as during a general strike).

But heat was only part of the story. Extreme rainfall and flooding also wrought havoc in July. China, for instance, faced intense summer downpours – a continuation of a trend that saw floods account for over 90% of the country’s $7.6 billion in disaster losses during the first half of 2025. In mid-July, remnants of a typhoon dumped almost a year’s worth of rain in parts of central China, breaching dikes and flooding 1.13 million hectares of cropland in Henan province. Meanwhile, in South Asia, monsoon storms triggered flash floods and landslides, disrupting local economies from India’s Himalayan foothills to Japan (which grappled with Tropical Storm Danas and other heavy rain events). And in North America, unprecedented rainfall over the U.S. state of Texas turned a holiday weekend into tragedy – the Hill Country flash floods (July 4–5) killed more than 100 people and caused an estimated $18–22 billion in total damage and losses.

The cascading impact of these disasters reverberated through global supply chains and commodity markets. Temporary port closures and shipping delays were reported where floods hit major transport hubs. Crop shortages (from heat and flood damage) began to drive up food prices, contributing to inflation worries. According to European Central Bank research, the extreme summer heat in 2022 had already increased food price inflation by about 0.7 percentage points in Europe – and similar pressures were feared in 2025 as key breadbasket regions baked in drought or were submerged by floods.

All told, July 2025’s climate events underscore an emerging reality: what was once considered “once-in-a-century” weather is becoming a yearly – even monthly – occurrence, and the economic fallout is mounting. Below, we break down the impacts by sector, highlighting how different parts of the economy – from farms and factories to hospitals and holiday resorts – have been affected by this month’s climate extremes.

Agriculture: Crops Wither and Food Costs Climb

Farms and farmers were among the first to feel July’s climate wrath. Extreme heat, drought, and erratic rainfall combined to hit agriculture on multiple fronts, threatening harvests and pushing up costs. In Southern Europe, a brutal early-summer heatwave saw temperatures soar above 45 °C in countries like Italy, Greece, and Spain, withering fields and orchards at the peak of the growing season. EU agricultural monitors reported that only Italy and Türkiye are expected to see significantly reduced crop yields this summer due to intense heat and water stress, while other parts of Europe have fared closer to average.

However, the outlook for summer crops (like corn, sunflowers, and soybeans) in much of Southeast Europe is poor, thanks to persistent spring drought and the July heatwave. In Hungary, Romania, and Bulgaria, soil moisture reserves were largely depleted by the end of June, disrupting the flowering and grain-filling stages of crops and leading to below-average biomass and yield projections. Farmers in these regions are bracing for smaller harvests, which could reduce exports and income for rural communities.

Conversely, parts of northern Europe faced the opposite problem: too much rain. Finland and Estonia experienced excessive rainfall in July that left fields waterlogged. This hampered fieldwork (farm equipment can’t easily operate on muddy ground) and raised the risk of fungal diseases in grains, potentially cutting yields or quality. Climate change is amplifying this whiplash between drought and deluge, often in back-to-back fashion – and farmers are struggling to adapt.

North American agriculture also went on a weather rollercoaster. Canada and the United States dealt with a patchwork of drought in the west, heatwaves in the central and eastern regions, and even unseasonable chill in some pockets. The U.S. Corn Belt and Western states have been mired in drought; by late July, fully 45% of America’s durum wheat and 62% of its barley production areas were in drought-affected zones.

Ranchers reported parched pastures and higher feed costs as irrigation water grew scarce. In the U.S. Southwest (Arizona, New Mexico, Nevada), extreme heat compounded the dryness, forcing some farmers to leave fields fallow or harvest early to avoid total crop failure. Meanwhile, the U.S. Northeast had an entirely different challenge: intense downpours and flash floods punctuated hot spells, which stunted some crops like corn and drowned others. New England farmers say that alternating heatwaves and heavy rains compacted their soil and delayed planting, hurting yields of vegetables and grains.

🚨 Antarctica’s forgotten neighbor is melting — climate alarm rings from Heard Island

Even regions known for milder climates saw surprises. In California’s normally warm Central Valley, fruit growers took a hit from an unseasonably cool spring followed by a summer heat spike. Cherry farmers in California lost up to 80% of their crop this year after an unexpected late frost in early 2025 destroyed blossoms. This rare cold snap – the flip side of climate volatility – shows that “climate disruption” isn’t just about heat; it’s also about greater unpredictability. For these farmers, the economic consequences include millions in lost revenue, potential layoffs of seasonal workers, and higher prices for consumers at the grocery store.

The spillover effect on global food prices is a major concern. Reduced wheat and maize harvests in key exporting countries can tighten supply and drive up commodity prices worldwide. Europe’s extreme heat in 2022 sent prices for staples like olive oil and cereal grains sharply higher, and 2025 may see a repeat. Analysts note that climate-related crop losses have contributed to the recent surges in international grain prices. Consumers could feel this in 2025 as higher costs for bread, pasta, and other essentials. Additionally, countries that rely on food imports might see their import bills rise, worsening trade balances and inflation.

On a positive note, some regions (like parts of France, Romania, and the Baltics) had adequate rain earlier in the season, which has kept winter wheat yields above average. Those bumper crops could offset losses elsewhere to a degree. But the overall picture is one of increased volatility. Farmers are responding by investing in adaptation – for example, planting more heat-tolerant crop varieties, adjusting planting calendars, and installing advanced irrigation and weather monitoring systems. These measures, however, come with costs that eventually pass through to food prices. In summary, climate change is quietly eroding global crop yields and raising costs year by year, and July 2025 was a stark reminder of how vulnerable our food supply is to weather extremes.

Energy: Power Grids Under Strain in a Hotter World

As thermometers soared this past month, so did the demand for electricity. Air conditioners kicked into overdrive in homes and offices across the Northern Hemisphere, triggering record-breaking power consumption that tested the limits of energy infrastructure. Utilities had to scramble to keep the lights (and AC units) on, while balancing the stress on generation plants and transmission lines.

The United States saw an unprecedented surge in power usage at the end of July. Amid a massive heat dome that settled over much of the country, Americans’ electricity demand hit an all-time peak of 759,000 megawatts on July 29 (topping even the previous record from July 2024). In Texas – a state notorious for both summer heat and rapid population growth – the grid operator reported demand nearing 82,000 MW in late July, the highest ever for that state.

🏆 The fall of a climate champion — biggest carbon surge in 15 years alarms scientist

This came dangerously close to the Electric Reliability Council of Texas (ERCOT)’s available capacity, prompting public appeals for energy conservation to avoid blackouts. Fortunately, no major outages were reported in Texas or other regions, thanks in part to utilities bringing extra generation online and consumers dialing up thermostats a bit. But the spike in electricity prices was unavoidable: in markets strained by demand, wholesale power prices jumped, which could eventually flow through to higher monthly bills for households and businesses.

Europe’s power grid faced a similar trial by fire (literally, in some cases). A June–July heatwave across Europe drove up electricity demand by as much as 14% in the worst-hit countries, as air conditioning – once considered a luxury in cooler climates – became essential for comfort and health. Electricity prices in parts of Europe doubled or even tripled on the hottest days.

For example, in Spain and France, utilities reported peak demand rising over 10% above normal July levels, forcing them to import power from neighboring countries at premium rates to meet the shortfall. The heatwave also exposed vulnerabilities: several nuclear power plants in France had to curtail output because the rivers used for cooling water grew too warm, while coal and gas plants across Europe strained under continuous operation, with some unplanned outages. In one striking example, electricity price spikes exceeded €400 per megawatt-hour on the hottest afternoons – roughly ten times the normal price – illustrating the economic stress on energy systems.

On the brighter side, Europe’s burgeoning renewable energy sector helped cushion the blow. June 2025 saw record solar power generation in the EU – about 45 terawatt-hours – thanks to the sunny conditions. During peak daylight hours, solar farms kept air conditioners humming and alleviated some pressure on the grid. This underscores a hopeful trend: investing in renewables and grid flexibility can pay dividends during climate extremes.

🌾🔥 The Price of a Warming Planet: How Climate Chaos Is Cooking Your Grocery Bill

Grid experts noted that heatwaves often coincide with abundant sunshine, which is an opportunity to store surplus solar energy (for example, in batteries) to meet the surging evening demand when people are still cooling their homes. Still, the nights remained warm too – and the wind doesn’t always blow – so Europe is keenly aware of the need for more robust grids, better interconnections between countries, and advanced demand management to ride out future heat-driven power crises.

Perhaps nowhere was the energy-climate intersection more dramatic than in China. In mid-July, an oppressive heatwave blanketed areas from Chongqing in the southwest to Guangzhou on the southern coast, an area home to over 200 million people. Air conditioning demand soared, and China’s national electricity load hit a record 1.5 billion kilowatts (1,500 GW) on July 16, breaking the previous peak by a wide margin. To put that in perspective, China’s power consumption at that moment was roughly double the entire electricity use of the United States. The government assured the public that the power system was holding up, though they warned of possible power rationing if the extreme heat persisted.

Memories are still fresh of China’s summer 2022, when a heatwave forced some provinces to impose rolling blackouts on factories to conserve power for residential cooling. This year, China ramped up coal and hydro generation preemptively. In fact, solar energy accounted for roughly half of the surge in June’s power generation as new solar farms came online, and hydropower output was slightly higher than last year (though still below 2022 levels). Even so, the strain was evident: provincial grids set new peak demand records more than 30 times during the summer. Chinese analysts likened the situation to a “stress test” for their energy infrastructure – one that will recur with increasing frequency as climate change fuels more intense heatwaves.

The economic implications of these energy stresses are multifaceted. In the short term, businesses face higher operating costs (for cooling and from volatile energy prices). Utilities may need to invest billions in grid upgrades and new power plants to handle new peak demand levels – costs that often pass to consumers via rates. Industrial productivity can suffer when factories pre-emptively slow down or when power quality issues disrupt sensitive manufacturing processes (for example, voltage drops can affect equipment). And in regions that did experience outages in past years, even brief blackouts meant losses for refrigerated goods, halted assembly lines, and so on.

On the flip side, some sectors see a temporary boost: sales of air conditioners and fan units in China more than doubled in July compared to the previous month, according to e-commerce data. Restaurants and cinemas reported higher foot traffic in some hot locales as people sought air-conditioned public spaces. These anecdotes show how consumer behavior shifts with the climate – an interesting dynamic where, for instance, a heatwave can spur spending on certain goods and services (cooling equipment, cold drinks, indoor entertainment) even as it imposes costs elsewhere.

In summary, July 2025’s extreme heat tested the resilience of energy systems worldwide. It highlighted the urgency of climate adaptation in the power sector: building grids that can withstand peak surges, diversifying energy mixes, and innovating in energy storage and efficiency. Investments made now could save trillions in avoided economic losses and downtime in the future.

Infrastructure: Flooded Roads, Melting Rails, and Burning Homes

Climate disasters in July struck at the physical foundations of our economies – roads, bridges, buildings, and utilities. Around the world, critical infrastructure proved both a casualty of extreme weather and a determinant of how costly an event turned out to be. Simply put, sturdy infrastructure can blunt economic losses, while vulnerable or aging infrastructure can greatly amplify them.

The Texas Hill Country flash floods over the Independence Day weekend offered a stark example. Torrential rains (up to 12 inches in hours) turned normally scenic rivers into raging torrents that washed away bridges, crumpled highways, and swept buildings off foundations. In one dramatic case, the Guadalupe River rose 30 feet in an hour, a wall of water that few structures could withstand. Entire rural communities were cut off as roads were submerged or destroyed.

💩 Microsoft’s billion-dollar climate bet: buying poop to fight global warming

The total bill for repairing homes, roads, and power lines in central Texas is estimated at $18–22 billion – and a big chunk of that is literal infrastructure rebuild costs. Beyond direct repair costs, the loss of infrastructure had ripple effects: road closures and bridge failures meant supply chain disruptions, as deliveries of goods were delayed or rerouted. Some communities lost access to clean water and electricity for days. AccuWeather’s analysis of the disaster noted that the economic loss figure accounts for not only property damage but also things like “major travel delays, tourism losses and damage to infrastructure”. Each closed road or downed power line translated to lost productivity and extra expenses.

On the U.S. East Coast, Tropical Storm Chantal delivered a similar blow to infrastructure, albeit at a slightly smaller scale. Chantal spun up quickly and made landfall in South Carolina on July 2 with heavy rains. It caused flash floods and widespread road closures across the Carolina. A section of State Highway 902 collapsed in North Carolina. Floodwaters caused the damage. This cut off a key route. Dozens of smaller bridges were also damaged. Culverts suffered heavy destruction. Cleanup will cost tens of millions. Reconstruction will take months or longer. The storm’s total economic toll was $4–6 billion. Infrastructure damage drove much of this cost. A collapsed highway means more than repairs. Commuters must take longer routes. Freight trucks face higher fuel and time costs. Hundreds needed swift-water rescues. Emergency services were heavily strained. Fire and rescue teams worked at full capacity.

In Europe, July’s extreme heat and wildfires also tested infrastructure resilience. Wildfires in Greece, Italy, and the Balkans not only charred forests but also threatened settlements and transport networks. In late July, as Greece endured its third heatwave of the summer, 52 new wildfire outbreaks erupted within 24 hours. Near Athens, fires raged in the suburb of Drosopigi, burning two houses and forcing evacuations in nearby villages. Firefighters struggled to contain blazes amid 44 °C heat and strong winds, with explosions reported as flames reached industrial areas (including factories storing flammable materials).

Damage to infrastructure included destroyed power lines leading to outages, and sections of highways closed due to low visibility and fire risk. On the island of Evia, fires prompted the evacuation of 138 people (including tourists) by boat from a beach when roads became impassable. Such emergency measures underscore how infrastructure – ports, roads, communication lines – is integral to disaster response. The cost to rebuild homes and utility networks in fire-affected Greek regions will add up, and the loss of timber resources (forestry is infrastructure of a sort too) carries economic value as well.

Heat itself can directly damage infrastructure even without flames. Across many countries, asphalt roads buckled and concrete pavements cracked under prolonged 40 °C+ days. Some cities experienced disruptions in public transit as railway tracks expanded and risked deformation (in extreme cases, rails can bend or “kink” in heat, forcing trains to slow down). In China, officials warned that sustained heat could soften road surfaces and even cause minor deformation in steel structures, although no major incidents were reported in July. In the U.S., July’s heat was blamed for a handful of highway blowouts (when pavement bursts due to thermal expansion), adding surprise repair jobs for state transportation departments.

⚡Clean energy crisis — EPA pulls plug on $7 billion “Solar for All” grants

The overarching theme is that infrastructure not designed for new climate extremes will continue to incur damage, leading to costly repairs and upgrades. Consider that many drainage systems in older cities were built to handle “20-year floods” – but now what used to be a 20-year flood (in terms of rainfall intensity) might happen every 5 or 10 years. This means under-capacity storm drains and levees, resulting in urban flooding that damages businesses and homes. July saw numerous instances of urban flash flooding, from New York basements to Beijing streets, due to short-term cloudbursts overwhelming drainage. Each such incident has a price tag in ruined goods, building repairs, and insurance claims.

The economic consequences of infrastructure loss go beyond immediate repair bills. In the Texas flood, for example, the local economy of the Hill Country will feel long-term effects because damaged campgrounds, parks, and historic towns reduce the area’s tourism appeal (more on tourism below). Businesses in inaccessible areas lose revenue each day a road is closed. There are also safety upgrades that authorities often implement after a disaster – which, while necessary, incur further costs. For instance, rebuilding a washed-out bridge might involve fortifying it against future floods, raising the price compared to a simple like-for-like replacement.

In summary, July’s climate events exposed weak links in our infrastructure, from transportation to utilities. They also highlighted the importance of investing in resilience – whether it’s building higher bridges, burying power lines (to avoid wildfire sparks or storm winds), using heat-resistant materials, or expanding drainage capacity. Every dollar spent on resilient infrastructure can save multiple dollars in disaster losses down the road. Given the trends observed, those investments can’t come soon enough.

Insurance: A Sector on the Retreat from Climate Risk

When disasters strike, it’s often the insurance industry that picks up the financial pieces – at least for those who are insured. But July’s barrage of catastrophes has further roiled an insurance sector that is already reeling from back-to-back years of heavy payouts. Climate change is reshaping the insurance landscape, making coverage costlier and harder to obtain in the areas most at risk.

Preliminary tallies for 2025 show that insured losses from natural disasters are at record highs. In the first half of 2025, global insured losses reached $81 billion – the most ever recorded for January–June. Events like the Los Angeles County wildfires in early January (which caused an astonishing $65 billion in damage combined) and the string of U.S. severe storm outbreaks have led to massive insurance payouts. By mid-year, the United States accounted for the majority of these insured losses, reflecting the high value of assets and widespread insurance coverage in the country – but also the severity of its disasters.

This trend continued in July: the Texas floods alone will generate significant claims for flood insurance, auto insurance (all those flooded vehicles), business interruption, and more. However, it’s crucial to note that many losses are not insured at all, especially flood damage. In the U.S., only about 4% of homeowners carry flood insurance under the national flood program, meaning most Texas flood victims will have to rely on federal aid or personal savings, not private insurance, to rebuild. This gap between economic losses and insured losses is one reason disasters can be financially devastating for individuals even if the economy as a whole absorbs the shock.

From the perspective of insurance companies, the risk calculus is changing. The frequency of billion-dollar disasters – traditionally rare, extreme events – has jumped. In the U.S., there have been 15 separate billion-dollar weather disasters in just the first six months of 2025. Such repeated beatings have led major insurers to reconsider their exposure. Throughout 2023 and 2024, and continuing into 2025, several large insurers have pulled back from high-risk markets. Multiple firms stopped issuing new homeowners’ policies in parts of California and Florida.

They cited wildfire and hurricane risks. Heavy losses caused these decisions. In July 2025, analysts and regulators raised alarms. Insurance companies are withdrawing from vulnerable regions. Premiums are rising sharply. Some risks are no longer covered. This has serious economic consequences. Without private insurers, many go uninsured. This leaves homeowners and businesses financially exposed. Others rely on state-run insurance pools. These pools strain public finances. Higher premiums act like a “climate tax.” Property in risky areas becomes more expensive. This can hurt real estate markets. Local investment may also decline.

We’re also seeing insurance costs get passed along to consumers and taxpayers. In parts of Louisiana and Florida, insurance premiums for a typical home have doubled over the past few years due to successive hurricane losses. After July’s severe weather, it’s likely that insurers will file for rate increases in affected states to recoup payouts. If private insurance is unaffordable or unavailable, more people end up in government-subsidized insurance programs (like Florida’s Citizens Property Insurance or California’s FAIR Plan). These programs sometimes run deficits that taxpayers may ultimately have to cover if a truly catastrophic event hits. Essentially, the financial risk is shifting from private companies to individuals and governments in many cases, as climate risks surpass what the traditional insurance model can handle.

The insurance sector also plays a role in driving adaptation – or at least it can. For instance, if insurers offer premium discounts for wildfire-resistant home improvements or for elevating a house in a floodplain, that can incentivize policyholders to mitigate risks. There are signs of this: one innovative policy launched in 2025 was a “wildfire resilience” insurance product that gives better rates to communities that thin forests and create defensible space around homes. Likewise, some flood insurers reward the installation of sump pumps or flood barriers. These measures, while somewhat niche now, could scale up as insurers seek to reduce claims by encouraging policyholders to protect their property proactively.

🔋 Tesla, GM Lead Battery Revolution as EV Sales Dip—Energy Storage Takes Center Stage

Despite these adaptations, the broader trend is worrisome. Experts like former California Insurance Commissioner Dave Jones have warned that if climate change continues unabated, insurance retreat could spark broader financial risks – for example, affecting the mortgage market if homes become uninsurable and thus unmortgageable. A recent Financial Times piece (July 2025) even asked “How the next financial crisis starts”, suggesting that climate-exacerbated insurance failures could have ripple effects through banks and real estate. That’s a hypothetical worst-case scenario, but it underlines how fundamentally climate risk is redefining insurance.

Finally, consider the psychological safety net aspect: insurance payouts often help communities rebuild faster after a disaster, keeping economies stable. If that safety net weakens (due to underinsurance or insurer insolvency), recoveries from events like July’s floods and fires might be slower and less complete. That has long-term economic consequences – neighborhoods might not be fully rebuilt, some businesses never reopen, and population may decline in hard-hit areas.

In short, July 2025’s events further confirmed that the insurance industry is on the frontlines of climate change’s economic battle. The past month’s heavy losses will factor into next year’s premiums and underwriting decisions. For policyholders, it’s a wake-up call to reassess coverage and preparedness. For insurers, it’s yet another data point in the argument that today’s climate risks demand new strategies – and a rapid transition to a lower-carbon economy – to keep losses manageable.

Labor: Lost Productivity and Worker Safety in Extreme Weather

Climate extremes don’t just destroy things; they also sap human productivity. July 2025 offered a vivid illustration of how extreme heat and other weather disasters affect the workforce and workplace, leading to economic losses that are more subtle than smashed buildings but significant nonetheless. Whether it was outdoor construction workers in a heatwave or factory employees idled by a flood, labor disruptions were a recurring theme this past month.

The most direct impact was from heat stress on workers. As large swaths of the globe broiled in record temperatures, millions of people who work outdoors or in non-air-conditioned environments faced dangerous conditions. Studies have quantified the economic cost of lost labor in high heat, and the numbers are striking. In India, for example – which wasn’t spared from heatwaves this summer – an estimated 182 billion potential work hours were lost in 2023 alone due to extreme heat. That is equivalent to the labor of 34 million full-time jobs just vanishing, a figure projected to grow by 2030 as global temperatures climb. While July 2025’s heat in India was not as headline-grabbing as in 2022 or 2015, many parts of the country still saw temperatures well above normal, slowing construction projects and reducing agricultural work hours (farmers often had to start pre-dawn and halt by midday).

In the United States and Southern Europe, authorities took emergency measures to protect workers during heatwaves. Cities like Seville, Spain and Rome, Italy enforced afternoon construction stoppages on the hottest days, and in the U.S., the federal Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) reminded employers of their obligation to provide water, rest breaks, and shade to outdoor workers. Despite these efforts, there were reports of heat-related illnesses and even a few fatalities on the job.

📉 Britain’s Green Future in Jeopardy—Reform UK Threatens to Rip Up Energy Contracts

Tragically, farmworkers and delivery personnel are often among the most vulnerable. We saw news of at least three worker deaths in June’s heat dome in the U.S. South, and July likely added to that toll. Beyond these human tragedies, the economic effect is that work simply slows down or stops during extreme heat. Productivity drops sharply once the thermometer passes roughly 35 °C (95 °F) – one expert noted that at those temperatures, a moderately active worker loses about 50% of their work capacity. Multiply that across an entire region in a heatwave, and you get a significant dip in economic output for those days.

Heat also affects indoor labor if facilities aren’t climate-controlled. Many manufacturing plants and warehouses are not fully air-conditioned, especially in parts of Europe and Asia where historically it wasn’t deemed necessary. In July’s heatwave, some European factories adjusted schedules to cooler nighttime shifts or even shut down for a few days to avoid unsafe conditions inside metal-roofed buildings. Office workers, meanwhile, might have been less productive simply due to discomfort or sleepless nights during heatwaves (surveys show that cognitive performance falls when room temperatures climb too high). All of this contributes to what economists call output loss – GDP that “could have been” if the weather had been normal. Research by the ECB, for instance, found that summer heatwaves can cause an immediate output loss of around 1% in the affected regions and that the losses can persist, with output still about 1.5% lower even two years later as knock-on effects continue. This counters the old assumption that after a disaster there’s a quick rebound; instead, heat may have lasting scarring effects on local economies.

Beyond heat, labor was impacted by other July disasters too. The floods in Texas and elsewhere meant that many people couldn’t get to work (due to road closures or evacuations) or their workplaces were destroyed. Service workers in tourist areas hit by wildfires or storms saw their shifts canceled as visitors fled. For example, when Greek islands evacuated tourists during wildfires, hotels and restaurants suddenly had no customers – and their staff effectively had no work until conditions normalized. In China’s flood-affected zones, thousands of agricultural laborers had to focus on emergency levee-patching and saving what they could of the crops, instead of normal production activities. There is also the aspect of lost labor from illness: the heavy wildfire smoke that blanketed parts of North America in June and July (from Canadian wildfires) led to respiratory problems for many, likely increasing sick days. A recent study highlighted that wildfire smoke exposure has significant economic costs due to increased mortality and health care, potentially costing hundreds of billions annually – which indirectly includes lost labor productivity.

Then there’s the human capital toll: people injured in disasters or suffering long-term health effects from heat (like kidney issues from dehydration or heat stroke) may be less able to work in the future. The Texas flash flood not only took lives but also caused injuries and trauma to hundreds of residents; some will be dealing with physical and mental health recovery that keeps them out of the workforce for extended periods. The long-term health consequences of heat – such as exacerbating heart and respiratory conditions – can also reduce labor supply over time if not addresseddw.com.

Economically, when labor productivity falls or workers drop out temporarily, businesses produce less and often profits suffer. Some sectors like construction and agriculture can sometimes “make up” for lost days by working overtime when weather permits, but there are limits. If a window for planting or harvesting is missed, you can’t recover that output. If a project deadline slips due to heat delays, contractors might face penalties. These micro-level impacts accumulate to noticeable macroeconomic effects. Analysts have begun factoring in climate adjustments to economic growth forecasts – for instance, one estimate suggests the recent European heatwave could reduce Europe’s 2025 GDP growth by about 0.5 percentage points, in part through labor effects.

In response, adaptation measures for workers are gaining attention. “Heat safety” laws and regulations are being debated and implemented in various places. The European Trade Union Confederation is advocating for an upper temperature limit above which outdoor work must stop (some countries already have guidelines like 38 °C limits). In the U.S., a federal heat workplace standard is under development, though some states have moved ahead with their own rules.

Employers are also adjusting by shifting hours (e.g., outdoor work very early or late in the day) and providing cooling breaks. These changes might slightly reduce total hours worked (for instance, a construction crew might cut a summer workday short), but it’s a necessary adaptation to keep workers safe – and ultimately it may be more economical than pushing workers to exhaustion and risking health emergencies on the job.

To sum up, the labor force is on the front lines of climate change. July 2025’s extreme weather showed how both the quantity of labor (hours worked) and quality of labor (productivity per hour) can decline under climate stress. Protecting workers – through better labor practices, technological aids like cooling gear, and of course mitigating climate change itself – is essential not just for humanitarian reasons but for maintaining economic momentum in a warming world.

Health: Heat Waves, Smoke, and the Mounting Health Care Costs

Climate change’s impact on health is often measured in lives lost, but it also carries a hefty economic price tag through health care costs and lost human capital. The past month provided sobering examples of how extreme weather translates into a public health crisis – and by extension, an economic one as well.

Heat-related health problems surged in many regions during July. Hospitals saw influxes of patients suffering from heat exhaustion, dehydration, and heat stroke. For instance, in the U.S. state of Maryland, July 2025 marked a five-year high for heat-related hospitalizations, with over 500 people treated in emergency rooms for heat illness during the month and 8 heat deaths recorded in July alone. By the midpoint of the summer, Maryland had tallied 1,200 hospital visits and 19 fatalities linked to heat – alarming numbers for a single state. Multiply that by the dozens of states and countries that experienced heatwaves, and the scale of the health impact becomes clear. Each severe case of heat illness can incur thousands of dollars in medical expenses, and extreme cases (like organ damage from heat stroke) can lead to long-term disability requiring ongoing care. Public health officials opened cooling centers and urged precautions (like checking on the older people, who are especially vulnerable). While these measures save lives, they also illustrate the resources that must be diverted to emergency response as the mercury rises.

Heat mortality is a tragic indicator. Europe’s late June to early July heatwave caused at least 2,300 excess deaths. More deaths likely occurred across the continent. Scientists link 65% of deaths to human-induced climate change. This tripled the death toll compared to preindustrial times. The human loss is immeasurable. There are economic costs too. Families lose breadwinners. Productivity drops. Emergency medical and funeral costs rise. Ambulance call-outs spiked in many cities. Hospitals added extra staff, often paying overtime. India faces severe heat regularly. A single intense heat day causes about 3,400 deaths in India. A five-day heatwave kills around 30,000. These deaths devastate communities. They also reduce economic contributors and human potential.

EV Buyers Blindsided: $7,500 Credit Gone as Senate Abandons Clean Tech Incentives

Another less obvious health impact of climate events is the mental health toll. Survivors of disasters like floods and wildfires often experience trauma, anxiety, and depression. These can translate into long-term health care needs (therapy, medication) and can affect economic productivity (someone struggling with trauma may find it hard to work or may need time off). The Texas floods in early July, for example, prompted discussions about providing mental health support to residents who endured the frightening flash flood and lost neighbors or family. AccuWeather’s economic loss estimate for that event even explicitly included “long-term physical and mental health care costs for survivors and families who lost loved ones.” This inclusion is telling – it recognizes that healing continues long after the floodwaters recede, and that too carries economic weight.

It’s also worth noting the strain on health infrastructure itself. Many hospitals are not built to handle relentless heat. In the UK (which had an unusually warm July), a significant number of hospitals lack air conditioning in patient wards. Doctors reported that when indoor temperatures exceed 26 °C, patient safety can be compromised and medical equipment (like medication fridges or computer systems) may fail. During previous heatwaves, some hospitals saw their IT systems crash due to overheating, adding chaos to already busy emergency departments. While we did not hear of specific IT crashes in July 2025, the NHS and other health systems were on high alert. Hospitals had to deploy extra cooling units and fans, an added operational cost, and in some cases, elective surgeries were postponed to reduce stress on staff and patients during peak heat.

Infectious diseases can also be exacerbated by climate events. For example, standing floodwater and warm temperatures are a breeding ground for mosquito-borne illnesses. In South Asia’s monsoon season, spikes in dengue or malaria often follow flooding. These public health impacts can linger for months after the initial event, potentially slowing workforce recovery and saddling communities with more health care costs. While July 2025’s immediate health headlines were heat and smoke, experts also keep an eye on any secondary disease outbreaks (none major have been reported yet, but the season isn’t over).

From a policy perspective, the health sector is calling for more heat adaptation and emergency preparedness. This includes simple measures like creating more cooling centers, distributing cool packs or oral rehydration salts during heatwaves, and having early warning systems for extreme heat (similar to storm warnings). Some jurisdictions are exploring naming and ranking heatwaves (as we do hurricanes) to raise awareness and preparedness. Meanwhile, smoke mitigation – such as community clean air shelters and better wildfire management – is becoming a priority in places like California and even New York after this summer’s crises.

In economic terms, the health consequences of climate change can act like a drag on growth. They increase health care spending (which might divert spending from other productive investments), reduce labor productivity (through sick days and impaired cognitive function in heat), and can even affect education (students don’t learn as well in extreme heat, affecting human capital formation). All these micro effects aggregate into macroeconomic outcomes.

July 2025 reminded us that protecting public health is an essential component of climate resilience. The investments we make in cooling infrastructure, healthcare capacity, and emergency response will pay off not just in lives saved but in dollars saved. One study in The Lancet has mapped the potential lives saved with heat action plans and found significant benefits. Every life saved or illness averted is also an economic positive, preserving the contributions that person makes to society.

Tourism: Vacations Disrupted by Heat and Disaster

For global tourism, July 2025 was devastating. Vacations were scorched or washed out. Climate change puts travel on the frontlines. Extreme weather makes destinations dangerous or unappealing. Popular tourist regions faced major disruptions. Financial losses hit the industry hard. Tourism thrives on stable, pleasant conditions. July proved those conditions are no longer guaranteed.

Figure: U.S. holiday tourism took a hit in early July 2025 when Tropical Storm Chantal struck the Carolinas. Heavy rains from the storm caused flooding. Beaches closed and airports shut down. Evacuations happened during Independence Day weekend. AccuWeather reported major tourism losses. Chantal’s impact added to its $4–6 billion economic toll. Thousands canceled or cut short vacations. Dangerous rip currents made coasts unsafe. Flooded roads blocked access to beaches. Hotels faced mass cancellations. Occupancy in coastal counties fell sharply. Many tourists stayed home or chose other destinations. The Carolinas will recover eventually. However, peak holiday week revenue is lost forever.

Europe’s summer tourist season was likewise literally overheated. Historic cities like Rome, Athens, and Madrid endured daytime highs well above 40 °C on multiple days. Instead of leisurely city tours, many travelers sought refuge indoors or adjusted their itineraries.

Tourists suffered heat strokes at popular sites. The Acropolis and the Coliseum had medical teams ready. Many visitors needed help. Last-minute cancellations increased in Southern Europe.

🌬️ Wind, Water, and Wonder: 8 Clean-Tech Creations You Need to See to Believe

Tourists from cooler countries postponed trips. Some chose alternative destinations. Cooler coastal areas saw more visitors. Some swapped Rome for Scandinavia. Revenue for tour operators dropped. Outdoor attractions saw fewer guests. Cafes lost business during peak heat. Streets emptied in afternoon hours. Extreme heat kept people indoors. Moody’s projected major economic losses. The 2025 heatwave could cut 0.5% of Europe’s GDP. Losses may reach 1.4% in Spain. Tourism is vital to Spain’s economy. Fewer travelers mean hotels and restaurants lose business.

Fires are worse for tourism than heat. Wildfires in Mediterranean holiday spots made global headlines in July. On Rhodes, fires forced mass evacuations. Thousands of tourists and locals fled as flames neared resorts. People dragged suitcases along roads. Smoke chased them from hotels. This was not the holiday they wanted. Greece estimated millions in lost tourism revenue. Airlines arranged emergency flights. Travel companies offered refunds and free rescheduling. Turkey’s Antalya region also faced fires. Parts of Sicily saw beach closures. Tourists were relocated for safety. Immediate losses included refunds and rescue costs. Fires also damage reputations. Future visitors may avoid high-summer bookings. Travel patterns could shift northward. Cooler destinations and mountain retreats may gain visitors. Classic Mediterranean summers could lose appeal.

Floods also hurt tourism. Heavy monsoon rains hit countries like Japan and India. Festivals and events were canceled. Japan canceled several summer festivals after typhoon downpours. Domestic tourists were disappointed. Small businesses lost revenue. In India, the Himalayan foothills faced severe flooding. Landslides closed pilgrimage routes. Tourists had to be airlifted. Uttarakhand relies on annual pilgrim visits. Each day the yatra was suspended caused losses. Hotels, guides, and transport operators all suffered.

Then there’s the less visible effect: tourist comfort. Even if a destination isn’t in direct crisis, extreme weather can reduce tourist spending. A tourist in a heatwave might skip that afternoon shopping spree or shorten their cafe sitting (resulting in fewer purchases). They might opt for indoor, possibly less local, experiences (like staying in their air-conditioned international hotel chain rather than venturing out). All these micro decisions scale up. On the other hand, some entrepreneurs are adapting – tours are being offered at dawn or night to avoid heat, and “climate shelters” in tourist zones (air-conditioned public spaces) are becoming part of tourism infrastructure.

Travel insurers had a busy month. Trip cancellations from natural disasters led to many claims. Some travelers recovered costs through insurance. Wildfires and storms triggered payouts. Insurers absorbed these expenses. Policies may become more expensive. Climate-related exclusions could increase. Some may deny coverage during active wildfire emergencies. Travelers might face stricter rules.

It’s important to note that tourism often bounces back quickly once conditions normalize – people return the next season, and rebuilding can be fast if funds are available. For instance, Greek authorities have become unfortunately practiced at quickly restoring tourist sites after wildfires. However, adaptation may be needed: marketing campaigns to shift peak tourist season earlier or later (to spring or autumn) are already being discussed in some heat-prone areas. In the long run, tourism might geographically pivot – with some summer hot spots becoming less desirable and cooler regions seeing new interest. That itself would have significant economic implications for communities dependent on tourist dollars.

Counting the Costs and Adapting for the Future

The economic consequences of climate change are here. They now cost billions each month. July to early August 2025 proved this clearly. Our economy is tied to the climate. One month brought many costly events. Deadly floods struck rich and poor regions. Heatwaves pushed power grids to the limit.

Workers also struggled in extreme heat. Wildfires threatened towns and tourist spots. Heat and smoke damaged public health. The global picture is alarming. July’s disasters may cost tens of billions. This follows a record-breaking first half of the year.

Every sector felt the strain. Agriculture saw reduced yields and harder operating conditions. This could raise food prices and import bills. Energy infrastructure bent but did not break. Emergency measures and price spikes were needed. This warns of future heat impacts. Physical infrastructure showed vulnerabilities.

Roads, bridges, and buildings need climate-resilient upgrades. The insurance industry is struggling to adjust. It must price the new normal of disasters. Some risks are now quasi-uninsurable. Labor productivity fell noticeably. Climate change is also a workforce issue. It affects overall economic growth.

Public health systems were tested. They coped but at rising costs. Treating heat-related illnesses added hidden expenses. Tourism faced another reminder. Extreme weather disrupts holiday plans. Revenue streams can vanish quickly. Many countries depend on tourism for survival.

One key takeaway is the importance of adaptation and resilience. Many of July’s worst impacts could be mitigated with the right foresight. Better urban planning can reduce heat. Green spaces help cool cities. Heat-reflective materials lower building temperatures. This makes heatwaves less deadly. Disruptions become less severe. Strong flood defenses are essential. Smarter land-use planning reduces risk. Avoid building in high-risk flood zones. This can prevent flash flood destruction. Texas showed why this matters.

Also Read:⚡ Clean energy dreams derailed? $4.9B Grain Belt Express loan scrapped in shock move

Improved early warning systems and evacuation plans can save lives and property when storms and fires strike. The events of this past month have undoubtedly added urgency to such measures. Policy responses are already underway. Governments are planning heat action strategies. Grid upgrades are receiving investments. Building codes are being adjusted for resilience.

Relief funds support hard-hit sectors. China expanded economic safety nets. These aid people displaced by flood projects. Direct compensation is promised for losses. Submerged farmland is included in payouts. Similarly, local authorities in India instituted work-break policies during extreme heat to protect workers and maintain some productivity. These are small steps, but point in the right direction.

Another takeaway is the interconnectedness of impacts. A heatwave isn’t just a weather event; it’s an economic event affecting energy, labor, health, and more all at once. A flood isn’t only a local disaster; it can ripple through supply chains and even global insurance markets. This means our response can’t be siloed.