🕒 Last updated on August 16, 2025

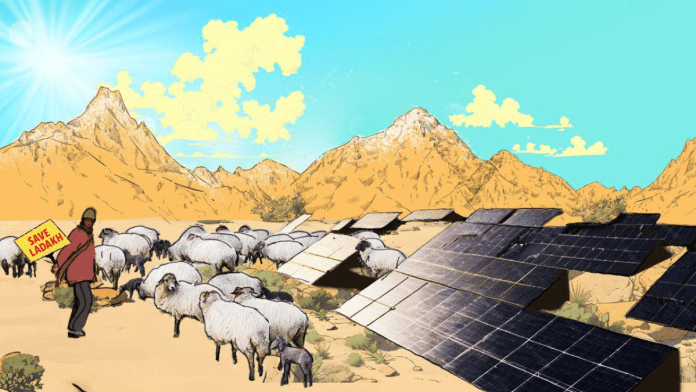

A massive solar and wind power project worth Rs 60,000 crore is being planned in the cold desert of Ladakh. It promises to bring clean energy to millions of people across India. But the project is raising alarm among Ladakh’s traditional herding families, who fear it could wipe out their pastures, their pashmina goats, and their way of life.

The project, called the Pang Solar Park, will cover nearly 48,000 acres of high-altitude grasslands with solar panels and wind towers. These grasslands are not just empty plains. They are the grazing grounds of pashmina goats, which produce the world’s finest and softest wool. For centuries, these goats have sustained Ladakh’s economy and culture. Now, that lifeline may be in danger.

Clean energy dreams in Ladakh

The Indian government has chosen Ladakh’s vast open spaces for building its biggest solar-and-wind park yet. With the potential to generate 9 gigawatts of solar power and 4 gigawatts of wind power, this project could supply electricity to millions and boost India’s clean energy targets. It is also linked to a new power corridor that will carry energy from Ladakh to Haryana, hundreds of kilometers away.

Officials say Ladakh’s clear skies, high altitude, and strong radiation make it one of the best places for solar power in the country. They assert that the project will not interfere with herding operations and that the right to graze will not be affected. But herders are doubtful. They argue that once solar panels and wind towers come up, their goats will not be allowed to graze freely. They also point out that no written guarantee has been given to protect their rights.

⚡America’s biggest banks slash fossil fuel lending by $24 billion in 2025 despite political pressure

The project is already taking shape. Transmission lines, offices, helipads, and worker camps are being set up. Bridges and roads are being reinforced to carry the heavy equipment needed for construction. By 2029, the government aims to make the project fully operational.

Pashmina is at risk

The meadows of Changthang are more than just pastures to the nomadic herders of Ladakh. They are the heart of their culture and livelihood. Every summer, families travel across mountain passes to reach these meadows where their goats, sheep, and yaks graze. From these goats comes pashmina, a fiber so fine it measures just 12 to 15 microns in thickness. It is woven into luxury shawls sold worldwide.

Around 250,000 goats in Ladakh produce nearly 50 metric tons of raw pashmina every year. This fiber is sold through cooperatives, cleaned, spun, and turned into garments that are exported across the globe. For about 7,000 families, this trade is their only stable source of income. The finest pashmina, collected from areas like Samad-Rakchan and Kharnak, even has a Geographical Indication (GI) tag. This means it is recognized as a unique product linked to Ladakh’s climate and heritage.

U.S. soybeans face a limited export window in fall months

If pastures are taken over by solar panels and wind turbines, herders say their goats will lose the space they need to graze. Without the goats, the pashmina industry—which is not only an economic activity but also a traditional skill passed down through generations—may collapse. Herders fear that with no alternative livelihoods, many families will be forced to leave their ancestral way of life behind.

Experts warn that shifting from high-voltage direct current (HVDC) to alternating current (AC) transmission lines, as planned recently, may need more land and cause even greater damage to fragile ecosystems. Locals also worry about the thousands of outside workers who will move in during construction. They fear this could overwhelm Ladakh’s limited water, housing, and waste systems while also changing its social fabric.

Whose land is it?

The land identified for the solar project is officially classified as common land. Nomads do not hold legal documents or ownership papers for these pastures, even though their animals have grazed here for centuries. Instead, the local council has the power to hand over the land to the government. And in this case, it has already done so.

This lack of land titles puts herding communities in a vulnerable position. Without legal recognition, they cannot demand compensation or rehabilitation if they are displaced. Herders say there has been little consultation, and most of the decisions have been taken without their consent or even their knowledge.

Hottest Month, Highest Costs: How Climate Extremes in July 2025 Shook the Global Economy

Studies from around the world show that large renewable projects often take over lands used by pastoral communities, a practice sometimes called “green grabbing.” Critics argue that while renewable energy is important, it should not come at the cost of traditional livelihoods, cultures, and fragile ecosystems.

In Ladakh, only a few nomadic communities remain, continuing a way of life that has lasted for centuries. They fear that once solar panels spread across the meadows, there will be no space left for their goats or for their culture to survive.

For now, bulldozers continue to move into Pang, worker camps are rising, and survey stones mark the boundaries of a mega-project. But in the silence of Ladakh’s high pastures, herders continue to wonder if their centuries-old bond with land and animals is about to be broken in the name of clean power.