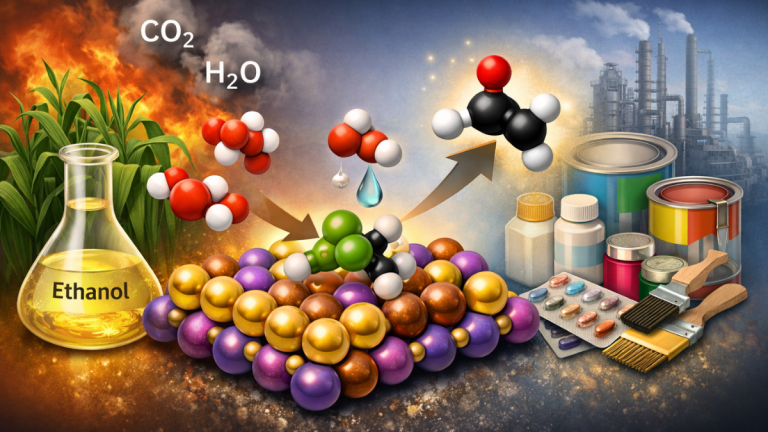

Gold is helping scientists turn plant-based ethanol into valuable industrial chemicals by keeping a delicate reaction under control. When ethanol reacts too strongly with oxygen, it burns into carbon dioxide and wastes energy; however, with precise control, it converts into acetaldehyde, a key ingredient in plastics, medicines, and paints.

Using a specially designed gold-based catalyst, researchers achieved about 95 percent efficiency while running the process at lower temperatures than conventional methods, demonstrating how cleaner materials can reduce waste and harsh industrial conditions.

Why ethanol matters for greener chemistry

Most acetaldehyde made today comes from fossil fuels. Factories usually start with ethylene, a chemical made from oil and natural gas. Ethylene then goes through a process that uses metals and chlorine-rich liquids to turn it into acetaldehyde. While this method works well, it has drawbacks. The chemicals involved can corrode equipment, create harmful byproducts, and depend heavily on fossil resources.

Ethanol offers a cleaner starting point. Many countries already produce large amounts of ethanol by fermenting plant sugars. In this process, microbes turn sugars from crops like corn or sugarcane into alcohol. Because plants absorb carbon dioxide as they grow, ethanol can be considered renewable when managed carefully.

Chemically, ethanol is a good match for making acetaldehyde. Both molecules have two carbon atoms. The change only requires removing hydrogen atoms while keeping the carbon structure intact. That sounds easy, but oxygen does not always stop when asked. Without control, oxygen keeps reacting until ethanol breaks down completely into carbon dioxide and water. This is like overcooking food until it burns.

Petrostates clash with climate goals as $160B warning issued over green shipping pact

Catalysts are the key to control. A catalyst is a material that speeds up a chemical reaction without being used up. In ethanol oxidation, the catalyst must encourage just enough reaction to form acetaldehyde and then stop. If it pushes too hard, valuable chemicals are lost. If it is too gentle, the reaction becomes slow and inefficient.

Earlier high-performing systems achieved good yields but often relied on toxic metals like chromium. These materials raise health and environmental concerns, especially when used in large-scale plants. This made scientists search for safer ways to guide the reaction.

How gold changes the reaction balance

Gold may seem like an unlikely choice for industrial chemistry. It is expensive and often thought of as unreactive. However, when gold is broken into tiny particles and placed on the right surface, it becomes surprisingly active. In ethanol oxidation, gold can help remove hydrogen atoms without pushing the reaction too far.

In this research, gold particles were placed on a special crystal structure called a perovskite. This structure is made mainly of manganese and oxygen. Some of the manganese atoms were carefully replaced with copper atoms. This small change had a big effect on how oxygen behaved on the surface.

The amount of copper mattered greatly. When there was too much copper, the surface became unstable. Copper atoms changed their form and lost their ability to cooperate with gold. When there was too little copper, oxygen activation was weaker. The best results came when about one-third of the metal sites were copper. At this level, copper helped oxygen become active but did not overpower the system.

The gold particles did not work alone. The most active reaction spots formed where gold sat close to copper and manganese atoms. These areas acted like teamwork zones. Oxygen molecules landed on the surface and became activated. Ethanol molecules then approached and lost hydrogen atoms step by step.

🌿 Beyond Batteries: Why Green Hydrogen is the Energy We’ve Been Waiting For

First, surface oxygen pulled hydrogen from ethanol, forming water. This step prepared the molecule for the next change. Then gold sites helped remove a second hydrogen atom. At this point, acetaldehyde formed and quickly left the surface. Because it detached fast, it did not stay long enough to react further and burn into carbon dioxide.

This balance helped the catalyst stay focused. It produced acetaldehyde instead of unwanted gases. The design avoided toxic elements and relied on the careful placement of common metals around gold.

Stability, temperature, and real-world performance

Temperature plays a crucial role in chemical reactions, as higher heat can speed up reactions but also increase unwanted side reactions that damage catalysts over time. Excess heat can cause metal particles to clump together, reduce active surface area, and allow carbon deposits to block key reaction sites.

In contrast, the gold-based catalyst operated at around 225°C, which is lower than many traditional processes, and it maintained stable performance for 80 continuous hours, a key requirement for industrial reactors that run without frequent shutdowns.

At the molecular level, the reaction depends on removing two hydrogen atoms from each ethanol molecule. The first step, which produces water, is slower and requires carefully activated oxygen. Copper helps in this stage because it binds oxygen less tightly than manganese, making oxygen more reactive and easier to release after the reaction.

Once water forms, small oxygen vacancies appear on the surface, allowing fresh oxygen from the air to attach and continue the cycle. Moderate copper levels supported this process, while too much copper disrupted the surface chemistry and reduced efficiency.

To better understand these mechanisms, researchers used computer models to simulate electron movement during the reaction. These models showed how gold, copper, and manganese work together rather than acting alone. While the catalyst performed well under test conditions, real-world use would still require longer trials with impure feedstocks.

ISS retirement set for 2030 as private space stations race to replace humanity’s orbital home

Even so, the results show that the process converts ethanol efficiently under milder conditions and can fit into existing industrial systems, although cost and gold usage remain the main challenges.