🕒 Last updated on October 27, 2025

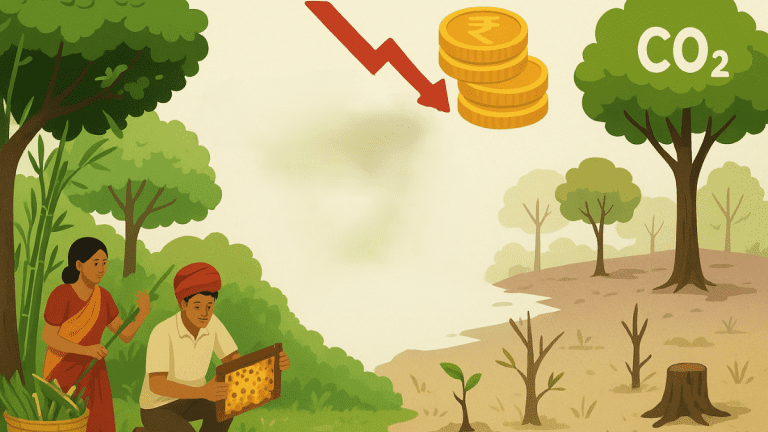

India’s forests are showing signs of quiet distress. A new government report has revealed that the total economic value of India’s forest products — both timber and non-timber — has dropped sharply over the past decade. Between 2011-12 and 2021-22, the combined value of timber and non-timber forest products fell by 21.4% in real terms. This means that, even after adjusting for inflation, forests are producing less value for the economy and the people who depend on them.

The fall is mainly because of a steep decline in the value of non-timber forest products (NTFPs). These are items like bamboo, honey, tendu leaves, herbs, resins, and other forest produce that local and tribal communities collect and sell. The report shows that the value of NTFPs dropped from ₹15,380 crore in 2011-12 to ₹7,790 crore in 2021-22 — almost half. This is a huge loss of nearly 49% in ten years.

In contrast, the value of timber — which includes wood used for furniture, construction, and other purposes — rose slightly by about 6.6%, from ₹15,330 crore to ₹16,350 crore. However, that small rise was not enough to make up for the heavy losses from non-timber products. Together, the overall forest product value across 22 states went down from ₹30,710 crore to ₹24,140 crore — a loss of ₹6,570 crore in constant prices.

Some states saw much bigger losses than others. Rajasthan recorded the sharpest fall in the total value of forest produce, losing ₹969 crore. Uttar Pradesh followed with a loss of ₹927 crore, and Punjab saw a drop of ₹764 crore.

Ireland’s silent revolution—forests reborn as wildlife sanctuaries, not timber factories

Experts believe that these numbers show deeper issues. The drop in forest value often means forests are becoming less healthy or less productive. It can also mean that access to forest products has become harder or that some natural areas are degraded and no longer provide the same resources they once did.

Falling Livelihoods and Forest Health

Behind these figures lie real struggles for people and ecosystems. In many parts of India, especially in forest-rich states, local and tribal families depend on NTFPs for their income. Items like honey, gum, or bamboo are often collected by hand and sold in local markets. When the economic value of these products drops, it directly affects livelihoods. Families that depend on forests may earn less money, face food shortages, or be forced to migrate for work.

In Punjab and Haryana, even though the forest area has slightly increased, the economic value of forest products has plunged. Punjab’s forest cover grew from 1,772 square kilometres in 2010-11 to 1,846 square kilometres in 2021-22. Yet, the state’s timber contribution to its economy fell from 5.94% to just 0.1% during the same period — a massive fall of over 95%. The value of non-timber products there also dropped by about 27%.

Haryana faced a similar trend. Timber’s share in its state economy fell from 0.30% to 0.09%, while NTFPs declined by over 97%. Himachal Pradesh, which has one of the highest forest covers in the country, saw a 47% drop in timber value. Though the area under forests there grew from 66.52% in 2013 to 68.16% in 2023, the forests are yielding fewer goods. This shows that more trees do not always mean healthier or more productive forests.

Across many regions, the story is similar: forest areas might be stable or even expanding slightly, but the value people get from them is decreasing. This suggests that forest quality is going down. Trees may be standing, but their ability to provide fruits, herbs, or wood is weakening.

US government rejects UN-backed carbon tax on international shipping

Carbon Value Rises but Tells a Mixed Story

While forest products have lost value, another kind of service from forests — carbon storage — has grown. Forests act as large carbon sinks, absorbing and storing carbon dioxide from the atmosphere. The report shows that the value of carbon retention services increased by 51.82% between 2015-16 and 2021-22. It went up from ₹409,100 crore to ₹620,970 crore during that period.

India’s forest cover now stands at about 23.6% of the total land area, and the average carbon stock per hectare has gone up from 99.99 tonnes to 101.85 tonnes between 2017 and 2023. This means forests are holding slightly more carbon than before, helping to slow down climate change.

However, not every state is gaining equally. Some states have seen a fall in carbon density — the amount of carbon stored per hectare. Kerala recorded a 22.9% decline, Karnataka saw a drop of 17.8%, Jharkhand about 17.1%, and Haryana nearly 17%. Madhya Pradesh and Karnataka also lost the most in terms of monetary value from carbon storage, at ₹3,045 crore and ₹2,332 crore respectively.

This contrast — where carbon storage is rising overall but dropping in several states — shows that forest health varies widely across India. While some areas are recovering, others may be losing vitality. The increase in carbon value may look positive, but it can hide deeper problems like biodiversity loss, soil degradation, or dying forest species.