Far below the ocean’s surface, in a remote stretch of the Pacific between Hawaii and Mexico, scientists have mapped 788 deep-sea species thriving in near-total darkness, many of which may be entirely new to science. Scientists made this discovery in one of the deepest and least explored regions on Earth, showing that even extreme environments support rich and complex ecosystems. At the same time, the finding raises serious concerns because deep-sea mining operations now target the same fragile seabed and could cause permanent damage before scientists fully understand these ecosystems.

A Hidden World Beneath the Pacific Ocean

Scientists made the discovery in a region called the Clarion-Clipperton Zone, often shortened to the CCZ. This area lies in the eastern Pacific Ocean and stretches across millions of square kilometers. The seafloor here sits more than 13,000 feet below the surface, making it one of the deepest habitats on Earth.

Despite the darkness and cold, the CCZ is full of life. Scientists identified 788 different species living on and within the seafloor. Some were observed directly, while others were identified only through DNA traces found in sediment samples. This data shows that many deep-sea creatures are still unknown or rarely seen.

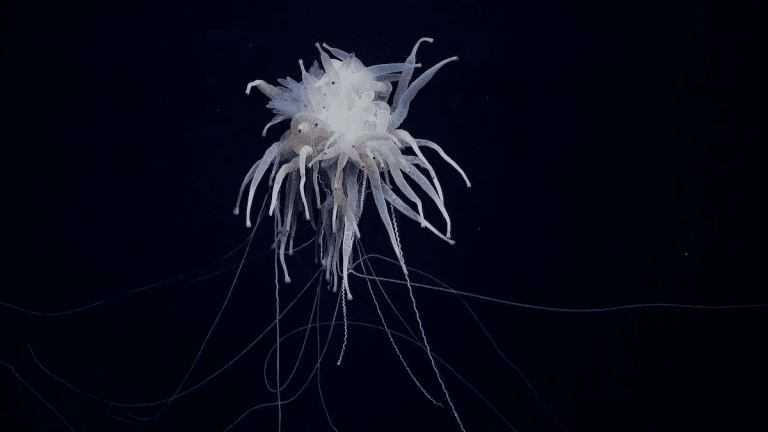

The species found include unusual and delicate animals. These range from soft-bodied sea cucumbers and pale sea spiders to slow-moving corals and fish adapted to crushing pressure. A large number of worm species were also recorded, with hundreds believed to be new to science.

Life in the abyss moves slowly. Food is scarce, and most animals survive on marine snow, which is made up of tiny bits of dead plants and animals drifting down from the surface. This organic material settles gently on the seabed and feeds entire communities. Because food arrives so slowly, many deep-sea species grow, move, and reproduce at a much slower pace than animals closer to the surface.

This slow rhythm makes abyssal ecosystems extremely sensitive. Even small disturbances can take decades, or longer, to heal.

Why the Deep Sea Is Under Growing Threat

The same area that supports this hidden biodiversity is also rich in valuable resources. The CCZ holds large amounts of polymetallic nodules, which appear as potato-sized rocks scattered across the seabed. These nodules contain metals such as cobalt, nickel, copper, and manganese that industries use in batteries, electronics, and renewable energy technologies.

As global demand for these metals increases, companies are looking to the deep sea as a new source. This has led to test mining operations in parts of the CCZ. These tests involve heavy machines that scrape the seabed and suck up nodules, along with large amounts of sediment.

When these machines move across the ocean floor, they create sediment plumes. These clouds of fine particles spread far beyond the mining site before slowly settling back down. This process can smother animals, clog their feeding structures, and alter the chemistry of the seabed.

Studies from test areas show that zones directly affected by mining tools experienced a sharp drop in animal populations. In some cases, the number of larger seafloor animals fell by more than one-third. Even in nearby areas not directly scraped, changes were observed in which species dominated the ecosystem.

Although the total number of species may appear similar, the balance between them shifts. Some species become rare, while others take over. This change reduces overall biodiversity and weakens the stability of the ecosystem.

Noise is another concern. Mining machines generate constant, powerful sounds that travel long distances underwater. While deep-sea animals may be the most affected, sound waves can also move upward through the water column. This raises concerns about impacts on whales and dolphins that rely on sound to navigate and communicate.

Fragile Ecosystems at Risk of Permanent Damage

One of the most alarming findings is how much life depends on the top layer of seabed sediment. Around three-quarters of abyssal species live in or just beneath this thin layer. This is exactly the part of the seafloor most disturbed by mining equipment.

Removing nodules also removes the hard surfaces that some animals use as shelter or attachment points. Unlike rocks closer to shore, polymetallic nodules grow extremely slowly. Some take millions of years to form. Once removed, they do not return on any human timescale.

While the world watches wars, China quietly rewrites the rules of global power

Many deep-sea species are specially adapted to stable conditions. They may not survive sudden changes in sediment, food supply, or water chemistry. Because these animals grow and reproduce slowly, recovery from disturbance can take decades or even centuries, if it happens at all.

Another challenge is that scientists are still learning how these ecosystems work. Some animals brought to the surface during research did not survive the rapid change in pressure. This means parts of the ecosystem remain poorly understood.

Researchers have also noted that some impacts may take time to appear. Areas affected by settling sediment plumes may seem unchanged at first. Over the years, however, slow shifts in species composition and health can occur, making damage harder to detect without long-term observation.

What is clear is that the CCZ holds far more life than once believed. The mapping of 788 species shows that the deep sea is not an empty wasteland but a complex and living environment. At the same time, the overlap between biodiversity hotspots and mining interests places this newly revealed world under serious pressure.

As exploration continues, the challenge lies in understanding what is being disturbed and how much can be lost before the damage becomes irreversible.